Adult razorback sucker. Reclamation photo by Mark McKinstry

Adult razorback sucker. Reclamation photo by Mark McKinstry

Story by Dave Speas, Adaptive Management Group

The endangered razorback sucker, named for its prominent dorsal keel, evolved in the Colorado River Basin over the last three to five million years and is found nowhere else in the world.

While hundreds of thousands of razorback sucker are found throughout the basin, the vast majority originate in hatcheries and are stocked by the truckload in various locations in several Upper- and Lower Basin states. While these fish readily spawn and produce larval fish every year, examples of their survival to adulthood are exceedingly rare. However, in autumn 2022, the Green River razorback sucker population got a significant boost in numbers of wild-spawned juvenile fish, thanks largely to the ongoing efforts of Reclamation and its partners in the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program.

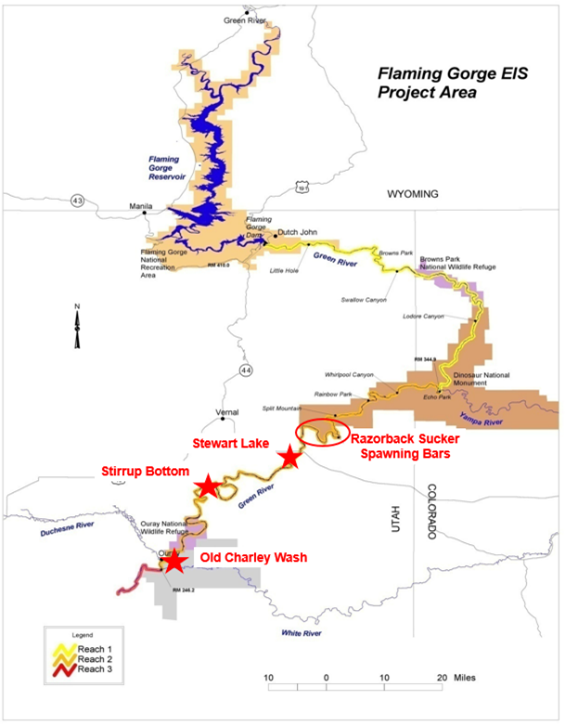

During late May and June of each year, newly hatched razorback sucker larvae emerge from spawning beds in the Green River near Jensen, Utah. Their odds of survival to adulthood initially rests with access to warm, food-rich floodplain wetlands along the river’s riparian corridor. Access to these rearing habitats, in turn, rests with spring peak flows, which need to be large enough to connect the river to its floodplains and provide a home for the tiny, weakly swimming larvae. Once established in these productive areas, a half-inch larval fish can reach five or six inches or more in just a few months, provided water quality remains optimal and density of predators is relatively low.

Reclamation has been working with Recovery Program partners since 2012 to ensure that the timing of spring peak releases from Flaming Gorge Dam coincides with the presence of razorback sucker larvae—a management action known as the Larval Trigger Study Plan, or LTSP.

Once the peak flows arrive carrying drifting larvae, biologists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources open flood gates to hundreds of acres of wetland habitat to let water and larvae in, then close the gates once flows peak to prevent the water and fish from flowing back to the river. After a summer’s worth of growth in these habitats, managers open the gates once again to drain the wetlands in the fall months, and juvenile razorbacks—now several inches in length—are collected, measured, weighed and microchipped for later identification. They are then released to into the wild where it is hoped they will mature and spawn as adults.

To the great and pleasant surprise of everyone involved, 2022 proved to be an exceptionally bountiful year for wetland-reared razorback sucker in the Green River, with old production records being shattered and entirely new ones established:

-

Stewart Lake, a 500+ acre wetland managed by Utah Division of Wildlife Resources for razorback sucker production under LTSP, produced a whopping 3,294 wild-spawned razorback sucker, almost doubling the number of fish produced there in the previous ten years combined. These were also the largest fish ever produced at Stewart Lake, averaging six inches in length.

-

Old Charley Wash near Ouray, Utah, one of the longest-serving wetlands utilized by the Recovery Program for endangered fish recovery, produced a record 615 razorback sucker, quadrupling the number of fish produced there in the last four years.

-

Stirrup Bottom, a wetland between Stewart Lake and Old Charley, was operated for LTSP by the Bureau of Land Management for the very first time in 2022 after construction of a water control structure by Reclamation in 2021. The wetland produced 551 fish, averaging a staggering nine inches in length, examples of some of the fastest wild razorback growth on record and certainly the biggest fish ever produced under LTSP.

Several factors converged to make 2022 a very special year for razorback sucker. First, operations under the Drought Response Operating Agreement (DROA) allowed for releases of 500,000-acre feet from Flaming Gorge Reservoir above and beyond what would normally be released in an otherwise moderately dry year. This volume of water was intended to help maintain lake elevations at drought-stricken Lake Powell, but a portion of it released during the spring peak period combined with Yampa River peak flows to create a 17,000 cfs (cubic feet per second) peak flow in the Green River near Jensen, Utah. This peak ascended over a period of seven days and overlapped completely with presence of larval razorback sucker. This was no coincidence, as biologists sampling the wetlands had alerted managers to the appearance of larvae May 21, and managers responded by increasing dam releases (including bypass) starting May 25. The result was a week’s worth of constantly increasing flows, which means a constant inflow of water and fish larvae into floodplain wetlands.

Another factor which undoubtedly favored high levels of razorback sucker production in 2022, was a significant degree of habitat management that occurred at Stewart Lake over the preceding several years. Fish need adequate space and food to grow rapidly and survive, and space had become scarce at Stewart Lake as cattails and other emergent vegetation had overrun the wetland in the last decade. Prescribed burns and other forms of vegetation management conducted since 2018 opened up considerable acreage of open water at Stewart Lake in 2022. Habitat was further enhanced through addition of supplementary water from Red Fleet Reservoir, which irrigators diverted to Stewart Lake during the scorching summer months. This action kept pace with evaporation sufficiently to maintain water quality.

Additionally, food availability for young razorback sucker was maximized through suppression of non-native abundance, which occurred through two mechanisms. First, all wetlands in the Green River corridor had been dry for at least a year, so non-native fish populations were not established when the wetlands filled in spring 2022. Wetlands with water control structures are usually drained each fall for this purpose. As water fills the wetlands during the spring peak, it also passes through specially designed screens which keeps larger, mostly non-native fish out of the wetland but lets the tiny razorback sucker larvae in. Through these actions the number of mouths to feed in the wetland is minimized, and razorback sucker work less to eat.

In summary, razorback sucker can thank a lot of hard-working biologists, dam operators, irrigators and other managers for their banner year of 2022. In a single summer, the joint coordinated effects of dam operations, habitat management and non-native fish management doubled the number of wild-spawned razorback sucker produced in wetlands since LTSP was first implemented in 2012. Reclamation operators with the Power Office and Flaming Gorge Dam expertly balanced the dual objectives of flows for endangered fish and additional water releases for DROA, and the integration of the two was instrumental in allowing large numbers of larval fish to access Green River floodplain wetlands. Most of these fish grew well over an inch per month throughout the summer months, reflecting ideal rearing conditions created through tireless efforts of biologists battling cattails and non-native fish, and irrigators who shepherded water to Stewart Lake.

All this activity may seem like a lot of work to raise fish, and when compared to rearing them in more artificial environments such as hatcheries, it probably is. But wild fish are much better at survival in the wild than their hatchery counterparts, and if it weren’t for the efforts of biologists and managers working on LTSP, there most likely wouldn’t be many wild-spawned razorbacks in the Green River. While biologists strive to understand why this is so, conservation actions such as LTSP are a viable means to improve the razorback sucker’s status.

The razorback sucker is currently being considered for down listing from endangered to threatened under the Endangered Species Act, and if approved, this milestone would be due in no small part to the many biologists and water managers who work every year to implement LTSP.